The fight against microplastics

14. abril 2022

Microplastics have been released into aquatic environment in very large quantities since large-scale production and use of plastics began in the 1950s.

Consequently, they have been observed in freshwater bodies and throughout the global ocean, in water, sediments and biota. This raises the question of whether there are potential negative effects on aquatic organisms, sufficient to cause an impact at the population level. It has also prompted concerns about the exposure of humans to microplastics, principally though ingestion of contaminated foodstuffs. (Extracted from: ICF Report for DG Environment of the European Commission).

All main environmental organisations worldwide are looking at options, new standards, or regulations for reducing releases of microplastics in the aquatic environment. (See documents from Bureau REACH, National Institute for Public Health, and the Environment (RIVM).

Microplastics is a term commonly used to describe extremely small pieces of plastic debris in the environment resulting from the disposal and breakdown of products and waste materials. The concern about microplastics centres on their potential to cause harm to living organisms in the aquatic environment and to accumulate in rivers and soils. The definition for microplastics is a synthetic polymer-based material that is not liquid or gas, in a size less than 5 mm in all directions. They can have a variety of aspect ratios, as near-spherical, sub spherical, irregular pieces, flakes, and fibres.

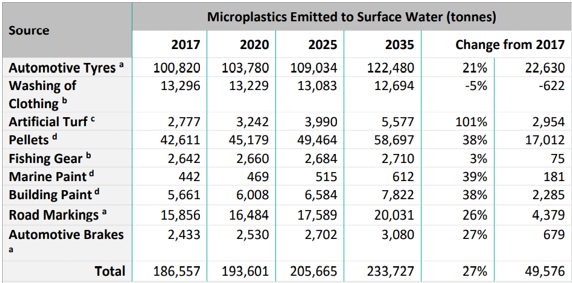

The main sources of microplastics emissions are automotive tyres, road markings, plastic pellets and washing of synthetic textiles. Other identified sources with less impact are artificial turf infills, paints and some detergent and cosmetic products.

Combined measures at the sources in all these segments can reduce emissions to surface water but is also important to consider downstream measures such as capture in storm water as this is expected to be the dominant pathway for microplastics emitted at sources.

Focusing on our flooring business, obviously our EPDM, TPV or SBR granules would be considered as microplastics but the use of SBR on the cushion layer in playgrounds and sport applications is helping to reduce quantities for one of the main sources released (automotive tires). A source of some concern would be infill applications for artificial turf fields that usually lose around 0.8% of infill material annually. With the dimensions and number of existing artificial turf sport areas worldwide that means a lot of tones released that may then enter drains, soil, or surface water.

The organic natural alternatives as cork, olives bones or coconut although a bit more expensive than SBR crumb rubber are a good performance solution for infill on artificial turf as the granules are standing-alone and would therefore avoid the microplastics restrictions, but when mixed with Polyurethanes for bonded flooring applications would re-enter the microplastic category as the substance attached to the outer surface make these granules inseparable particles of microplastic.

Luckily at our flooring applications the granules are bound on a continuous carpet flooring, and they are not normally released in significant amounts. Even if the installation is not entirely correct and there are some granules crumbling, the amounts potentially released are quite below the emission coming from all other sources or applications.

So, regarding our flooring business, first thing first, use the right proportion of binder and the one with the right viscosity for the climatic conditions of installation and you will avoid granules crumbling. If you are suffering granules crumbling, you can always use a topcoat to end the process.

Using a geotextile membrane as a separation layer before laying the first cushion layer may be a good environmental recommendation as a measure to protect the soil from any of the flooring materials and make things easier when material must be disposed at the end of life.

Other mitigation measures are simple to achieve during the design and construction of the surfacing area or the turf field; traps for drains, good housekeeping with spills regularly cleaned up and a site designed to prevent granules migrating outside of the area, are all simple but effective measures.

Finally handling and disposal of infill or flooring materials at the end of life must be carefully considered and planned by the installers and owners.

In conclusion we must try to remove the problem at the different sources.

Once microplastics are released into the environment there are several pathways they can take towards the aquatic environment and several sinks on these pathways that can retain them. There is still considerable uncertainty about how microplastics move around urban and rural environments, especially when they are not directly released into sewerage systems.

Some microplastics that enter the sewage system can be captured in wastewater treatment facilities and captured within sludge, that is applied to land or incinerated but there is no known method of removing microplastics from sewage sludge.

Unfortunately, also some microplastics may enter the aquatic environment directly without any being removed.

A lot of us may have children or grandchildren and we would like to think that we will leave them a planet that they can enjoy as much as we have been able to do in our childhood and youth, but that is a task that depends on all of us everywhere in the world and we don’t have to wait for more demanding regulations or standards.